R

E

V N

E

X

T

While the contemporary art discourse of late has headed into a global discussion on transcultural art practices, narratives of the 20th century still prevail within the perpetually retrospective view of Chinese art history. This was evident in 3 Parallel Artworlds: 100 Art Things from Chinese Modern History (2015)—an outstanding publication published this January by Hanart TZ Gallery, one of Hong Kong’s preeminent art spaces that celebrated its 30th anniversary just last year. The opus is one that can certainly be added to the boundless archive of scholarly books on China’s most tumultuous century.

The ambitious 483-page book sets itself apart as a one that is based on predominantly Chinese scholarly research, featuring contributions from seminal figures in the field, such as Shanghai University professor Wang Xiaoming and conceptual artist Qiu Zhijie. Stemming from academic discussions between Hangzhou-based curator Gao Shiming and Hanart TZ Gallery owner Chang Tsong-zung, the publication is based on the theoretic premise of the 2014 exhibition “Hanart 100: Idiosyncrasies,” which showcased 100 Chinese artworks from Chang’s collection, spread across three separate venues in Hong Kong. The book posits an interrelated development of “three parallel art worlds” in 20th-century China: a pre-modern art world; a socialist art world; and an art world fuelled by globalization. As Chang discerns in the book’s introduction, the publication “seeks to delineate the major forms of art practices that inform the Chinese cultural imagination today,” thereby challenging the chronology of art history as we know it.

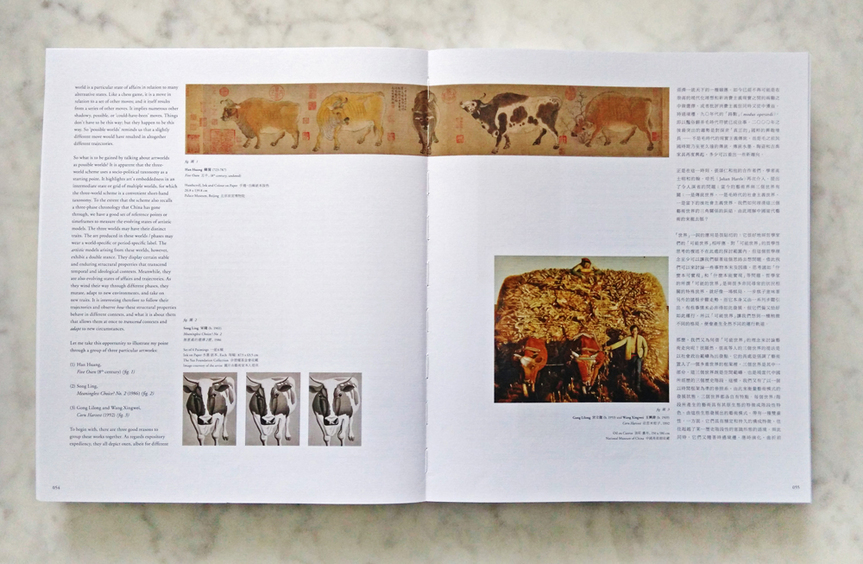

In the book, 12 essays and scholarly writings discuss the premise of intertwined art narration. Starting off the broad spectrum of articles are two authors, Russian avant-garde art specialist Boris Groys and Harvard professor Eugene Wang, both of whom take practical approaches in addressing the postulated “three worlds.” In “A Post-Socialist Utopia: Pawel Althamer’s Golden Humanity,” Groys describes Polish artist Pawel Althamer’s project Common Task (2009)—a performance where the artist recruited friends and neighbors from his hometown to travel the world in golden overalls—as an example to illustrate the ambiguous merging of post-socialist art forms with capitalist values in Eastern Europe. Wang examines oxen paintings from the eighth century, the 1980s and the ’90s, respectively, in his essay “Three Worlds: What Trajectories Do They Project?” Here he traces the stylistic and ideological development of the animal’s depiction and what he calls the “trajectories”—or, in other words, their influence on the evolution of art throughout their respective time periods.

The artworks from “Hanart 100” are the illustrative focus of the general discussion in 3 Parallel Artworlds and take up an extensive part of the publication. They are introduced by Chinese curator and artist Liu Tian’s writings, which elaborate on the curatorial concept and how the arrangement of the 100 selected artworks came to be since the project’s inception in November 2013. At first glance, the works seem irritatingly scattered across numerous themes created by Gao, with names such as “The People,” “Home Land” and “The Body.” However, once familiarized with the idea of art clusters that formed the “Hanart 100” exhibition, the groupings are deciphered as ones that defy old perceptive structures that cling to definitive historic boundaries. Instead, they open up a new associative mindset to the three “worlds” discussed in the book. To take an illustrative example, “The People” section assembles, among many others, the modern woodcut Raging Tide Series no.3: Press Gang of Able-Bodied Men (1947) by Cultural Revolution-era artist Li Hua, along with Taiwanese artist Wu Tien-Chang’s photograph entitled Companions for Life (2002). Both are extraordinarily disparate works that are connected by their essential depiction of “the traces of human" and the "traces of People,” that Gao Shiming epitomizes in a corresponding ode. The same interwoven examination has been applied to artworks collected under the theme of “The Word,” which have been “over layered, eroded [and] disordered.” Here, associations can be drawn between Wu Shanzhuan’s Wu Shuo Ba Dao (1985) and Daoist painter Hung Tungs’s hanging scroll Cosmic Diagram (c. 1970s). These are two artists who, although widely divergent in their political and religious views, are similarly engaged in using the power of words and images as a form of universal media, oscillating between meaninglessness and definitive ideology.

Spread from 3 Parallel Artworlds: 100 Art Things from Chinese Modern History, 2015. HUNG TUNG, Cosmic Diagram, c. 1970s, ink and color on paper, 147 × 41.8 cm. Photo by Billy Kung for ArtAsiaPacific.

In addition to the theoretical approaches provided in understanding this herculean publication, the third part of the book also includes very personal standpoints, like ink painter Qiu Zhijie’s account of his developing interests in the traditional medium. In his words, “Four different recipes . . . provided all the nourishment I needed in my youth: traditional scholarship, folk culture, the legacy of socialism, and globalism,” thus resulting in combining all three worlds, a solution he defines as “omnivorous.” Furthering this chronicle of intimate histories are Sun Quan, art activist and assistant professor at National Kaohsiung Normal University, and May Bo Ching from Taiwan, who is a history professor at Guangzhou’s Sun Yat-sen University, who both call into question the book’s underlying implications of “diaspora” and “division,” by elaborating on the politics and identities of belonging.

An exhaustive publication attempting to address the challenging topic of distorting the linear development of art history in China, Hong Kong and Taiwan, 3 Parallel Artworlds is not meant to be an effortless read. Rather, the book is impressive with a structure comprising a curated catalogue, an academic analysis and a remarkable chronology of Hanart TZ’s vast exhibition program, ranging from “The Stars: 10 Years” in 1989 to the major touring exhibition “Power of the Word” initiated in 1999. As an innovative yet heavy alternative to recent image-laden coffee table books in the field of 20th-century Chinese art, 3 Parallel Artworld signifies an extensive, even self-critical contribution to the art scene and scholarly, more inclusive consideration of China’s turbulent art history.