R

E

V N

E

X

T

Circuses, the Caucasus, and Contemporaneity: Interview with Taus Makhacheva

Through her dynamic multimedia works, Moscow-based Taus Makhacheva, whose family hails from Dagestan in the Northern Caucasus, comments on issues related to identities, homelands, memories, and post-Soviet modernity. For example, with a menu that included edible paper and a lollipop shaped like Vladimir Lenin’s head, her performance Stomach It: Menu and Performance (2017) interrogated the politics of food and the Soviet regime’s starvation of Ukraine and the Caucasus from 1932 to ’33. Her acclaimed video Tightrope (2015), of a man walking a tightrope across a deep canyon while holding copies of paintings from the Dagestan Museum of Fine Art, highlighted the precarity of museums and cultural heritage. Both Tightrope and Stomach It were shown at the 2017 Venice Biennale’s international art exhibition, “Viva Arte Viva,” as meditations on how the present is continuously shaped by sins of the past. Among Makhacheva’s more playful pieces is an ASMR spa, presented at the 2017 Liverpool Biennale. There, visitors received facial treatments while a cosmetologist whispered stories of artworks that have disappeared throughout history. Quick Fix, which debuted at the 2019 Armory Show in New York, involved Makhacheva’s alter-ego, Super Taus, engraving blank trophies for lucky visitors who won at a dice game, celebrating their unrecognized accomplishments. Built into all of these works is a sense of empathy and irony, cultivated through the collaborative processes that bring the projects and performative experiences to life.

Most recently, Makhacheva has been exploring the history of Soviet circuses and their representations of social life in the Soviet Union. Her research entailed conducting interviews with retired performers from the Baku State Circus and gathering materials from the Baku National Archive. Her findings were reflected in “Charivari,” her solo show at Yarat Contemporary Art Centre in Baku. With reference to charivari, a term that denotes a centuries-old practice where an individual is mocked by their neighbors via a discordant musical performance, as well as the final act of a circus performance, the artist imagines a moment in which the fantastic is real, where society is inverted, and wonder replaces cynicism. I spoke with the artist on the occasion of the exhibition about her research, artistic process, as well as the evolution of her practice.

How did you arrive at the topic of your solo show “Charivari”?

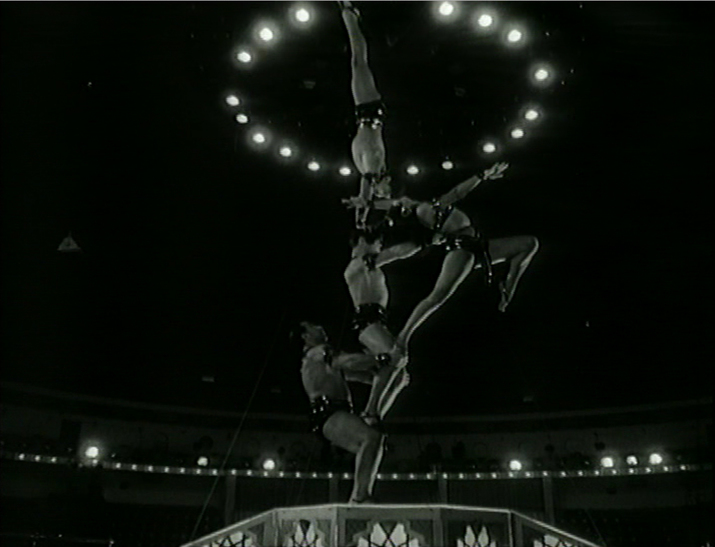

I love the Russian State Archive for photographs and documents, and I often rummage through things just hoping for a great discovery. When I was doing research there ages ago, I came across a documentary film called National Circus from 1967. It was very peculiar because it represented the different republics of the USSR through circus troupes. There was a famous circus dynasty called Nazirov Group doing pyramids with Orientalist costumes; a tightrope walkers’ group; and a clown from Uzbekistan, wearing an Uzbek robe, who was making fun of a Western-looking clown. I thought these subverted representations of racial identities and the societal dynamics within the USSR were quite funny. That is where the project started.

Then I came [to Baku] in early 2018 for a research trip, and I treated the city as a studio. I went to Gobustan, the mud volcanoes, where there is this incredible sauna that is only for men. I peeked in [their collection] of strange objects, which covered every surface of the building. I also spent time with lots of artists, especially Farhad Farzaliyev, who is part of the collective Unbound, and Andrey Misiano. A lot of the [ideas about mining cultural identity] came through in these ways. I also encountered the story of a Berber family who had a lion and kept it at home. I started thinking about human cohabitation with animals. This cemented my focus on circuses, which are a good prism through which I can talk about contemporaneity, especially in the Caucasus. That is what my works are essentially about.

What is the role of storytelling and personal narratives in the show “Charivari”?

Recently, I have worked a lot with writers. It is something that I enjoy. I invited Alexander Snegirev, who I love, to pen the show’s audio piece [which comprises stories about the circus, and accompanies the main installation]. I submitted to him pages and pages of scenarios for circus performances, as well as interview transcripts, and old photographs. We discussed what these materials could become. I wanted to write about the circus of the past, an imaginary circus, and the circus of today, which is why we have completely different audio acts incorporated into the final installation. We have a VR circus, a segment with a talking horse, and a short story about synthetic bears who started working at the circus but wouldn’t obey the trainers. You could call it magical realism because it is completely crazy and ridiculous.

All of the objects in the show add to this fantastical narrative. The components of the main installation appear to be fossilized but they could also be from the future. At the same time, I was thinking about the work as a drawing in space. It is the largest installation that I have ever done so it was a big experiment for me, but it was the only way to approach the work that made sense. The work talks about animal rights, the future of the circus, social problems, and family relationships in the Caucasus, but through this spectacle on stage.

Could you speak a bit more about the practice of charivari?

It is a term that signifies the final act of the circus when everyone comes together and performs at a crazy speed. It also refers to a ritual in Britain and France where neighbors within a community shame someone who has done something wrong. So there is satire and also a cannibalistic feel to it.

How do you interpret post-Soviet modernity in the Caucasus?

There is a story in the work about a canteen where all the foods are made from oil. It raises the question of why we use oil for machines when we could use it for food. I read that researchers are investigating how to extract edible proteins from oil. I was chatting with someone the other day and they said that during the Soviet era they used to make caviar out of crude oil. It sounds very fantastical—I haven’t fact-checked the information but I love it.

More precisely, I find it interesting how someone can say something and then someone says something else—this is how myths are produced, and this process reflects a society that can’t find a system. This turbulence is why I’m interested in the idea of post-post-Soviet futures. Everything is shaking—in the Caucasus and I think the rest of the world. We are in this era when we can’t attach ourselves to what happened during the Soviet era. But what is the way forward? There are multiple possibilities. Many worlds exist at the same time. There is patriarchy floating next to other worldviews like equal pay for women, for example. That is not only symptomatic for the Caucasus but also our time. That is what I was trying to highlight when I was working on the text with Alexander.

In another one of the short stories, there is a pyramid. A strongwoman accountant stands with each leg on an elephant. Around her neck is a chain with a box, in which there is a robe, slippers, a microwave, and a jacuzzi. Above the strongwoman is a female clown, and further up is a tightrope walker, circus director, the wife of the director, the daughter of the director, and the husband of the daughter of the director who has been promoted to the master of ceremonies, and who is in a cake. On top of the cake is a rose, and on top of the rose there is a fly in a silver cape. The narrative is about family relations, and simultaneously balanced and unbalanced structures. At the very bottom of the pyramid are hamsters on silver chariots that keep the circus going at all times.

Installation view of TAUS MAKHACHEVA’s “Charivari,” at Yarat Contemporary Art Centre, Baku, 2019. Photo by Pat Verbruggen. Courtesy the artist and Yarat.

Has this exhibition prompted any thoughts on how you will go about your future projects?

I often wonder what the font size of my name should be on the credits list for my projects. My work brings many people together and I know exactly what was done by everyone and what was done by me. When I was doing research for this show my studio manager Kristina contributed so much. Moving forward, I will have to think more about what agency is, how much authorship I hold, and what my collaborators’ roles are. Let’s see.

It is also very new for me to be working directly with objects. The 2017 Liverpool Biennial was one example where all of my sculptural installations were made by Alexander Kutovoi, who is a fantastic artist. I have a very different relationship with materials now, yet I see how it folds into my body of works with all of the types of people I have collaborated with in the past. I’m excited that my practice is becoming more varied. I look forward to seeing how else I can play.

Taus Makhacheva’s “Charivari” is on view at Yarat Contemporary Art Centre, Baku, until September 29, 2019.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.