R

E

V N

E

X

T

There is an unlikely combination of colors—shades of pink, red and gray, side by side—that belong unmistakably to the paintings of Philip Guston, who first achieved recognition in the 1950s as an abstract expressionist of the New York School. Yet that same palette, and a bold but wobbly line, carried over to the figurative paintings he slowly transitioned toward making during the late 1960s—a time when the gospel of avant-gardism preached only abstraction. In these iconic, countercultural paintings, Guston developed an alternative American world of symbolic forms including clocks, watches, cigarettes and boots, Ku Klux Klan-hooded figures, as well as cartoonishly slim and hairy limbs, all in surrealistic, often comically grotesque arrangements, which emerged partly as a response to the upheavals of the time. The exhibition “A Painter’s Forms, 1950–1979,” presented at Hauser & Wirth in Hong Kong, draws from works from the period of significant shift in the artist’s practice. ArtAsiaPacific spoke to Musa Mayer—daughter of Philip Guston, curator of the show, and author of a memoir on her father—about the works on view.

Installation view of PHILIP GUSTON’s “A Painter’s Forms, 1950–1979” at Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong, 2018.

As the curator of “A Painter’s Forms, 1950–1979,” how did you go about selecting the almost 50 paintings and drawings to show at Hauser & Wirth in Hong Kong?

We began by looking at the works in the Estate of Philip Guston to find the most representative works of my father’s career that could be used for an exhibition like this. It might sound like a somewhat limited selection, but I had always made sure to keep a number of works for an exhibition opportunity like this one.

It’s far more complicated to seek loans from private collections and museums, a process we had recently been involved with for the large museum exhibition, “Philip Guston and the Poets,” which was presented at Gallerie dell’Accademia during the 2017 Venice Biennale. We didn’t want to exert the energy, time and resources required then to borrow work for this show, and as it turned out, I feel we’ve mounted a representative survey covering the three decades we wanted to, with work that remains in the Estate.

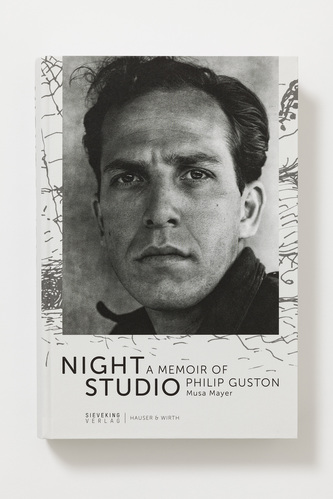

Your book Night Studio: A Memoir Of Philip Guston was originally published 30 years ago (and will be released by Hauser & Wirth in Chinese). Has your perspective on your father’s artworks changed since the publication of your book, or over the course of your creative life?

I think that during a lifetime—or half a lifetime—probably everyone’s perspective about their parents change, as does the meaning of their parents’ influences on their lives. If anything, my appreciation of my father’s contribution to the history of art and my own love of his work has deepened over these 30 years as I come to understand him more deeply.

The feelings I had of loss and deprivation, of having to share his attention with his work and the other demands of his life, have resolved over time. I am now in my mid-70s and the concerns that I felt in my 30s are really no longer present. So I look at the book affectionately as the work of my younger self who was working through all of these issues at the time.

The reception of Guston’s paintings by art professionals and audiences has evolved over the decades, with a deeper appreciation for the progression in his approach to painting. What do you think, or hear from others, are specific resonances of his paintings today?

Well, as you say, attitudes to Guston’s work really have evolved as art itself has evolved. When his late work was first introduced, there was a strong reaction against it because of certain prevailing critical theories and opinions that were prevalent in the late 1960s and ’70s. But in part because of my father’s late work—along with other forces in the art world—there is now a receptiveness to much more diversity and expression in art, so I really think that were he working today, his late work might have been embraced sooner. That doesn’t take away from the appreciation that so many artists have expressed of his courage in following his inner dictates, and creating the work important to him despite the rejection of the art world during the last decade of his life.

I think also that the painterly qualities of his work and his love for all periods of art is evident in his painting, and is a part of what the art world responds to in his work today. Great painting is timeless.

Is there one work in the exhibition that is your favorite for either artistic or sentimental reasons?

That’s a difficult question because I really chose this exhibition to reflect my own favorite work. That being said, I think there are certain works that are more resonant to me than others. One painting I really love is Smoking I (1973), which is a self-portrait of the artist contemplating his realities and smoking (as was his want)—it just has this sense of his personage that I respond to. But there are other works too: Riding Around (1969) is a real masterpiece that was included in the first exhibition of his figurative works, held at New York’s Marlborough Gallery in 1970. Most of the paintings in that show are now in museum collections and major private collections, but this is one that we’ve kept, and that I cherish.

A painting I chose to highlight within the exhibition is an untitled small panel depicting a hand with a finger writing in blood. It is from 1968, a very turbulent time in the United States and to which my father’s late work was in part a reaction. I think it’s just a powerful image that evokes the horror of violence.

Installation view of PHILIP GUSTON’s “A Painter’s Forms, 1950–1979” at Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong, 2018. Photo by Vincent Tsang.

How do you imagine your father would have reacted if you had told him that in the year 2018 his works would be exhibited at a gallery in Hong Kong?

It is hard to know. I know that he was absolutely thrilled by the retrospective [at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art] that opened shortly before his death in 1980. In fact, even given his very poor health, he kept himself alive long enough to see that show and have that experience. He died just three weeks after it opened. So the idea of a retrospective or survey being brought to a new audience would have been thrilling and surprising to him.

And imagine what it would be for an artist to realize, decades after his own death, works that had been completely rejected in his lifetime that he knew were powerful would be accepted and celebrated. It’s a vindication, not just this exhibition but the many exhibitions that have happened over the past nearly 40 years. I only wish he could be here to take in the appreciation his work now commands.

HG Masters is the editor-at-large of ArtAsiaPacific.

The exhibition period of Philip Guston’s “A Painter’s Forms, 1950–1979” has been extended. The show is on view at Hauser & Wirth, Hong Kong, until August 25, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.