R

E

V N

E

X

T

Shanghai-based artist Wang Tiande has earned critical acclaim for his unique visual language, which draws from and reimagines ink-painting and calligraphic traditions. Wang was one of the first artists to radically present Chinese calligraphy in the form of an installation with his iconic conceptual work Ink Banquet (1996)—a table set for eight people, covered in ink-washed strips of paper. He forged his signature idiom in 2002, after he accidentally dropped ash on a sheet of Chinese paper when lighting a cigarette and noticed the beauty of the burn marks. Wang thus embarked on a series whereby each work typically comprises two sheets of paper layered one atop the other. On the surface is a landscape and calligraphic inscription created using the burn marks of incense sticks or cigarettes; the composition of the bottom layer is based on the image on top, and is rendered with ink and brush. What results is a complex work that challenges traditional precepts of ink-painting and calligraphy. Wang has since devoted his practice to further developing his layering methods. His subsequent series have incorporated stone rubbings and classical calligraphy, inviting viewers to reflect on the relationship between past and present. On the occasion of his exhibition “Awaiting” at Alisan Fine Arts, Hong Kong—the fourth solo show that the gallery has presented for him since 2003—Wang spoke to ArtAsiaPacific about his new works, collecting his thoughts on the future of contemporary ink.

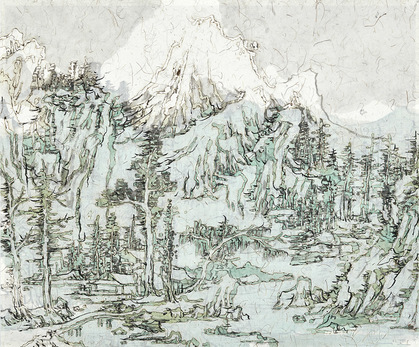

WANG TIANDE, Early Snow in the West, 2017, Chinese ink with burn marks on layered rice paper with calligraphy by Xu Liang (Qing Dynasty), 202 × 90 cm.

Some of your 2017 and 2018 works, presented as part of “Awaiting” at Alisan Fine Arts, incorporate classical works of calligraphy. Could you tell us about the inspiration behind your latest creations?

By chance, in November 2013, I saw a pair of album leaves by Chinese painter Dong Qichang (1555–1636) at a friend’s place. I had a flash of inspiration. It immediately dawned on me that I could create works in connection with classical calligraphy. From that day on, I began to collect Ming- and Qing-dynasty calligraphy. One of the works in the exhibition, Early Snow in the West (2017), incorporates a piece of calligraphy by Qing-dynasty artist Xu Liang. I acquired it at auction last year. It is quite large in size and is beautifully written—I consider it to be the best work in my collection! I was initially a bit reluctant and sad to part with it. However, because of my long relationship with the gallery, and with collectors in Hong Kong, I made the decision to juxtapose this special piece—rather than a print of it— alongside my own landscape. The painting that I created has a strong connection to the city. It is how I imagine Hong Kong island looked like two hundred years ago.

The format of the nearly four-meter-long work After the Snow (2018), is different from other pieces in the show—it is displayed on a slanted plinth, and its top and bottom layers are not mounted together—could you tell us a bit about it?

Yes, it’s the first time I created a work where the two layers are not mounted together. As a result, the top surface is not completely flat. It was my intention for the viewer to observe more closely and appreciate the raw and tactile nature of the paper. The display format encourages one to interact with the work—one has to walk around the plinth from the lowest to highest point to view it.

Could you speak about the use of color in your new works?

I started experimenting with color six to seven years ago, but wasn’t able to achieve something I was satisfied with. In fact, it was quite a painful process. But I persevered and kept trying. It was during this period that I happened to be studying the late landscapes by Wang Yuanqi (1642–1715), an artist whom I particularly admire for his skill in creating incredibly rich textures in his paintings. I was inspired to do the same. I adjusted the steps in my creative process and finally came up with a solution for applying colour. I was thrilled with the result.

I used malachite mineral pigment in the two works A Cold March (2018) and After the Snow in Fuchun County (2017). They both evoke the sudden cold spell of early spring.

Should we be expecting to see more color in your future works?

Yes, after working for over ten years with mostly black ink, I would like to start using a bit of color.

You always come up with interesting titles for your exhibitions. The title of your solo show “Over Mountains and Across Valleys” at the Guangdong Museum of Art in 2015 comes from the lyrics of a Taiwanese pop song. Could you speak a bit about how the title of the present exhibition came about?

While preparing for this show, I was being chased by the gallery to send them images and information for their marketing materials. One day, while driving, I was waiting at a red light. I sent a WeChat message to the gallery staff: “deng wo yi xia” [“wait a moment”]. A couple minutes later, I found myself waiting again at a red light. I decided right then that this would be the exhibition title. I later realized that it holds a much deeper meaning. In China today, many artists—not just those practicing ink art—are so impatient to make a breakthrough and achieve success. Especially for artists of similar age to myself, it is crucial that we constantly reflect upon our artistic practices and choices. An artist must have integrity and a sense of responsibility towards history.

You spoke earlier about the source of inspiration behind your new works and collecting classical calligraphy. Could you tell us about your collection and how collecting influences your artistic practice?

I have been collecting for around ten years—in addition to calligraphy, I have also bought Qing-dynasty steles and paintings. Although I studied classical works of calligraphy and painting at university, it’s not the same as acquiring a piece and bringing it home where I can thoroughly research its history and background. It’s like having a dialogue with a particular artist from antiquity—I can learn about his brushwork, seal impressions, the type of paper he used, and his way of thinking and emotions. This process always brings me much joy!

I feel very grateful for these last few years of collecting. The knowledge I have gained has enabled me to avoid looking at tradition in a superficial manner, but instead with great respect and reverence. My own works have been significantly enriched by this process.

If you could collect any artwork, what would it be?

A work by Bada Shanren (1626–1705). I love the artist’s simple visual language, and unique use of space, form and composition. His work always has the power to unleash a certain creative energy in me. If I could own just one of his paintings in my lifetime, it would make me so happy!

You’re based in the bustling city of Shanghai, how do you manage to create works that are so quiet and contemplative? Could you speak a bit about the environment you work in?

Realistically, it’s impossible to truly escape from the hustle and bustle of urban life. That said, my studio is in the Songjiang district, the outskirts of Shanghai. The surroundings are very quiet and peaceful. More importantly, it is the region where some of the late-Ming-dynasty master painters such as Dong Qichang (1555–1636) and Chen Jiru (1558–1639) are from. I like to think I can imbue some of their artistic spirit and creativity in my own work.

What do you think are the qualities that make a good artist?

First, one must appreciate every stage of creating art. Many artists become disheartened when they haven’t achieved a desired level of success at a particular stage. Secondly, it is important for an artist to have a certain faith or religion, as this gives one a deeper and more spiritual perspective on both life and art. A good artist must also be fiercely independent in their quest to create.

How do you think the genre of contemporary ink will continue to develop in the future?

As our society becomes more developed and technologically advanced, there is an appetite to more deeply understand tradition. It is only after understanding classical history and culture that a society can mature and develop. In China today, there is a growing interest in the country’s artistic heritage, from classical paintings to calligraphy, antiques, furniture and architecture from the Ming and early Qing dynasties. Through this renaissance of traditional culture and aesthetics, I think that in the next ten years, contemporary ink will no doubt develop further. I don’t think this only applies to China. Other Chinese-character-writing countries such as Japan and Korea are also taking on this approach of reflecting upon one’s own traditions.

Wang Tiande’s “Awaiting” is on view at Alisan Fine Arts, Hong Kong, until May 5, 2018.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.