-

From Current Issue

-

- Editor’s Letter Fire in the Heart

- Reviews I Gusti Ayu Kadek Murniasih

- Reviews 11th Seoul Mediacity Biennale: “One Escape at a Time”

- Dispatch Networked China

- One on One Monira Al Qadiri on Yukio Mishima

- Essays The rise of independent art spaces in pandemic-era Shanghai

- Features Tuan Andrew Nguyen

- Table of Contents

- Web Exclusives

- Archive

- Subscribe

R

E

V N

E

X

T

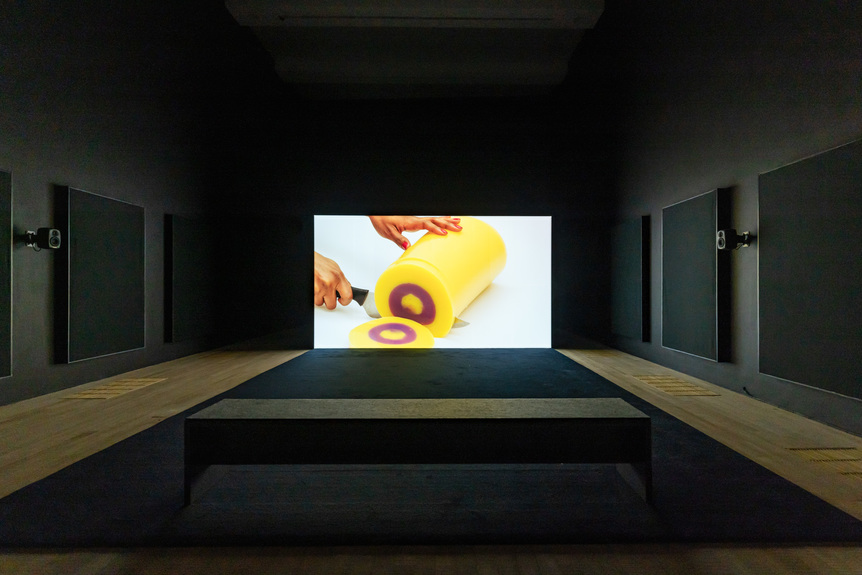

MIKA ROTTENBERG, NoNoseKnows, 2015, still from single-channel video installation with sound and color: 21 min 58 sec. Copyright the artist. Courtesy Mike and Kaitlyn Krieger Collection.

New York-based artist Mika Rottenberg has made a name for herself with her humorously surreal films and installations interrogating production, circulation, and value in our era of unchecked capitalism and hyperconsumerism. From the early days of her career, Rottenberg has homed in on the commodification of the (typically female) body, as expressed by enigmatic characters who engage in repetitive, unusual forms of production, from transforming red-painted nails into maraschino cherries (Mary’s Cherries, 2004) to inventing a dubious hair-growth tonic (Cheese, 2008). “SNEEZE,” staged at Tai Kwun Contemporary, includes four video works from 2012 to 2019 that continue the artist’s investigations into excess, surveyed together for the first time in Asia.

“Cleaned-out store and abandoned factory”

Where to begin with Mika Rottenberg’s films? Sizzling goo? A woman who can sneeze out pasta? Tiny quesadilla people? “SNEEZE” featured all of the above and more, seen in four video installations created by the artist over the past nine years.

There’s a pronounced maximalism to Rottenberg’s cinematic universe—sounds, colors, and textures abound as motley characters knead, squelch, spritz, and smash their way through robotic and arcane labor in grim factories and windowless rooms. Previous exhibitions have seen those absurd settings materialize at the venue, so it was surprising to see relatively sparse installations at Tai Kwun’s sizable space. Thus the floor-to-ceiling displays of tinsel and trinkets at a Chinese wholesale market seen in Cosmic Generator (2017) translated to near-empty wire racks at the exhibition entrance, decorated with a deflated plastic palm tree and straggling fairy lights, while the pearl-farming facility in NoNoseKnows (2015) manifests as a metal door and several sacks of pearls in a dingy antechamber. Both videos conflate images of material excess to scenes of bodies shackled to meaningless, dematerialized production. While profuse set pieces would have located viewers in the videos’ abundant present, the cleaned-out store and abandoned factory evoked at Tai Kwun suggested the lean aftermath. One assumes the downsized installations were a result of pandemic-related logistical concerns or the artist’s attempts at lowering her carbon footprint; in any case, they were appropriate mise-en-scènes for our plague year of toilet-paper shortages and shuttered businesses. OPHELIA LAI

“Gratuitous”

Theoretically, we should not exist. According to physicists, the Big Bang created equal amounts of matter and antimatter. When the two met, they should have annihilated each other. And yet here we are, surrounded by stuff. Entering Mika Rottenberg’s “SNEEZE” is to step inside a feverish reflection of the world, choked in an excess of materials, the sources of which appear to be magic.

In NoNoseKnows (2015), a woman’s sneezes become plates of glistening noodles and rice. To stimulate her production, a female worker, sitting among laborers at a distant Chinese pearl farm, winds a crank that powers a fan, which blows flower pollen into her face. Watching the transformation of her excretions into consumables, I was reminded of surrealist Georges Batailles’s problematization of society’s inability to expend energy in truly meaningless ways. This creates the cancerous capitalist loop of incessant production, based on use value.

Yet, Rottenberg averts explicit anti-capitalist critique. In Spaghetti Blockchain (2019), she even indulges viewers with ASMR, aided by materials such as luscious puffs of candy floss melting into a grill and wobbling jelly rolls. Perhaps these sensorially soothing scenes provide audiences with respite from constantly creating use and meaning (for those who don’t have to write about it for their jobs, anyway). And in the act of simply watching, viewers honor their subsistence in a universe that is gratuitous in the first place. CHLOE CHU

Installation view of MIKA ROTTENBERG’s Sneeze, 2012, single-channel video installation with sound and color: 3 min 2 sec, at “SNEEZE,” Tai Kwun Contemporary, Hong Kong, 2020–21. Copyright the artist. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth, New York / Los Angeles / Zurich / London / Somerset / Hong Kong / St. Moritz / Zürich / Gstaad / Southampton.

“Weirdness and novelty”

Mika Rottenberg’s Sneeze (2012), a short video of men with swollen probosces achoo-ing a lightbulb, slabs of meat, and rabbits onto a desk, suggests that even during an airborne pandemic, a sneeze can be much more than just 40,000 horrifying aerosolized droplets. In her longer video NoNoseKnows (2015), the links between the human body’s productions, environmental contamination, and global commodities production are vividly fleshed out in surrealist tableaus. A middle-aged White woman sits before a fan that blows pollen off potted plants until it induces nose excretions of pasta and noodles. The culinary surfeit piles up around her while in the cramped basement below Chinese workers in puffy jackets crank the fan, artificially inseminate oysters, and harvest and sort pearls in what could be a critical portrayal of the global labor market.

Yet instead Rottenberg emphasizes weirdness and novelty over the banality of inequality, elaborating on the unlikely material and cultural connections created by the internet (here, visualized as a “series of tubes”) in Cosmic Generator (2017), which features a cart-pushing street vendor whose concoctions are portals to wholesale markets in China full of plastic goods and Chinese restaurants in border-straddling Calexico. The politics of labor are not so much an issue as material. The weirdly wonderful secretions of the global Plastocene are experimented upon in a product testing lab in her most recent video, Spaghetti Blockchain (2019)—brightly colored, foamy, crisp, or gelatinous in texture, their sounds are satisfyingly varied, ASMR-inducing, and even polyphonic in the case of the exoticized female Tuvan throat singer standing in the mountains. The new materialism of the 21st century has made products of us all. HG MASTERS

“Mechanization of the body”

I wasn’t sure if it was the spring weather in Hong Kong or Mika Rottenberg’s video that was making my nose itch as I watched her video Sneeze (2012), which features sneezing men with huge, clownish noses. Well dressed in suits and ties, their loud and dramatic sneezes seem to be an embarrassment, as sneezing in public (in both pre- and post-Covid times) is often considered awkward or impolite. Yet with all the objects that they sneeze out—lightbulbs, raw meat, and adorable bunnies—the video puts the audience in a curious position of anticipation that makes us rethink our social protocols and etiquettes.

Rottenberg’s more recent “sneezing” video, the 22-minute NoNoseKnows (2015), furthers this idea in an industrialized setting, combining a fancy dining room with an assembly line in a pearl factory in China. A bulky, White woman sniffs pollen from a fan and sneezes pasta out of her nose, as Chinese women in the factory laboriously keep the fan spinning. Here, the supposedly uncontrollable act of sneezing becomes a kind of mechanical production. The video could be a clever gesture toward “the contemporary conditions of labor and exchange” in a globalized economy, as explained in the exhibition booklet, but it also directs my attention to the mechanization of the body in an urban, industrialized environment. For years I’ve learned to ignore my allergies as I live in a polluted city, but Rottenberg’s videos remind me of my own body. PAMELA WONG

“A surrealist universe”

Mika Rottenberg’s exhibition at Tai Kwun starts with a small party-supply shop display that appears to have been raided, evoking recent episodes of empty grocery stores worldwide. The shelving structures extending across the walls and ceiling were bare save for a few plastic trinkets. A critique of excessive consumerism, prodigal manufacturing, or both? Rottenberg explores this in her video installations, sending viewers down the rabbit hole to a surrealist universe that caricatures problems of mass production, globalization, and capitalism.

The sense of exorbitance recurs throughout. In Cosmic Generator (2017), seemingly endless tunnels are portrayed along with booths overflowing with artificial flowers and other unnecessary goods. NoNoseKnows (2015) exemplifies indefinite cycles of commodity manufacture and wastage, as well as the extraction of resources and talent by developed countries to oil their own gears. A Caucasian woman in her office repeatedly sneezes out cooked dishes, her labor supported by a group of Chinese women in the space beneath strenuously working to fan her nose. In Spaghetti Blockchain (2019), the absurd juxtaposition of colorful jelly being slapped at and foam being salted makes one wonder: should we do things, just because we can? Finally, Sneeze (2012) features men ejecting an assortment of objects from their noses, another show of inane superfluity. Funnily, amid a pandemic, the work took on new meaning, as the echoing soundtrack stirred nervous glances from mask-donning viewers turning to check who had just sneezed. Yet, how much has the pandemic really changed the way we think and live? Consider, for instance, how homebound consumers have turned to fanatic online-shopping, even for art. Have we learned anything at all? LAUREN LONG

Ophelia Lai is ArtAsiaPacific’s associate editor; Chloe Chu is managing editor; HG Masters is deputy publisher and deputy editor; Pamela Wong is assistant editor; Lauren Long is news and web editor.

Mika Rottenberg’s “SNEEZE” is on view at Tai Kwun Contemporary, Hong Kong, until March 31, 2021.

To read more of ArtAsiaPacific’s articles, visit our Digital Library.